You may be surprised to know that when I teach in undergraduate and adult ed situations, I actually deemphasize the importance of knowing Greek, Aramaic, and Hebrew for reading the Bible. I do this for two reasons:

First, the people to whom I am speaking will likely never attain proficiency in any of these languages; therefore, I want to reassure them that they can have a meaningful experience reading the Bible in English.

Second, in the circles within which I have travelled, I have found that appeals to “the original languages” are typically empty rhetorical devices designed to privilege one reading over another with the benefit that nobody listening can actually check you.* Indeed, nine times out of ten the statement “what the Hebrew/Greek actually means here…” will be followed by some world-class bullcrap.

That said, I also give the caveats that you should always check a couple different translations as a control and you should always be suspect of innovative readings that play off of a single word or turn of phrase. One important issue to understand is that English may be ambiguous where the Hebrew/Aramaic/Greek is not and vice versa.

I found an excellent example of this in my vacation reading. I checked out several books on teaching methodology including Teaching the Bible as Literature (Christopher-Gordon, 2002) by Roger Baker, which I hoped might have a couple activities worth borrowing. In the foreword, Baker illustrates his approach to the Bible with some tales of Elijah (1 Kgs 18-19) culminating with the wind, earthquake, and fire passing him on the mountaintop, followed by a “still small voice” (1 Kgs 19:12; KJV). Baker comments:

Notice how “still small voice” is punctuated. There is no comma between still and small. Instead of the voice being still and small, it is, after all, a small voice. It is “still” a small voice, in the English translation.

English ‘still’ may indeed function as either an adverb or an adjective. Further, adverbs usually occur in the spot before the adjective. The lack of a comma, therefore, leaves the grammatical function of ‘still’ ambiguous, and if Strunk and White were responsible for translating the KJV then I would agree wholeheartedly that this was a significant omission.

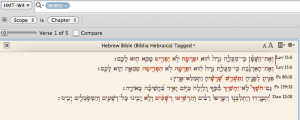

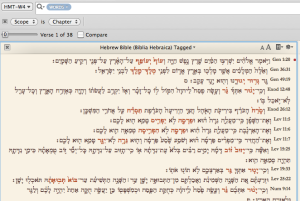

Since the KJV is generally a word-for-word translation, however, it is highly unlikely that the translators intended to render the adjective דְּמָמָה from the phrase קוֹל דְּמָמָה דַקָּה as the adverb ‘still, yet’ (Heb עוֹד).** Indeed, if you check the NRSV translation you will find “a sound of sheer silence” with no adverb, which should give you pause about this theory (see also the LXX φωνὴ αὔρας λεπτῆς and the Vulgate sibilus aurae tenuis).***

That said, something about this did interest me, which led to a day-long rabbit trail reading about the history of English punctuation and the KJV. In short, the punctuation in the original 1611 KJV seems to be inconsistent at best, and an attempt was made at standardization for the 1769 text. Of course, English punctuation in general was still in a state of transition during this period. In the 16th century, its function was primarily rhetorical rather than grammatical — similar to the Masoretic system, punctuation was intended to guide the oral performance of the text. For instance, in the Matthew-Tyndale Bible (1537), 1 Kgs 19:13 reads (see here; you want pgs 22-23):

“And after the fyre / came a small still voice.”

There are only two punctuation marks used in this text. The period (.) marks the end of the sentence and the forward slash (/) indicates the major pause similarly to the athnach. The shift toward a more grammatically precise punctuation system can be attributed to those continental humanists who “demanded a more exact disambiguation of the constituent elements of a sentence” (Parkes, Pause and Effect:Punctuation in the West, Univ of California Press, 1993, 88). This approach was apparently introduced to English by Ben Jonson’s 1616 English Grammar (see here) which was published posthumously in 1640.

So what is going on with the KJV? First I checked to be sure that “still small voice” was original to the 1611 KJV here. Next I looked for precursors. Interestingly, the Geneva Bible (1599) reads “A still and soft voice,” one of the options Baker would have preferred for a double adjective. The other version that influenced the KJV translators was the Matthew-Tyndale I quoted above, which read “a small still voice.”

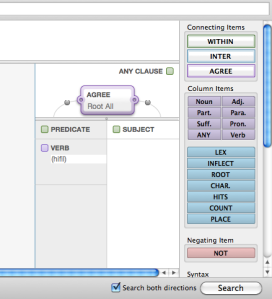

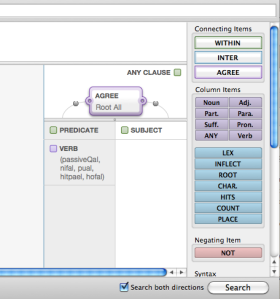

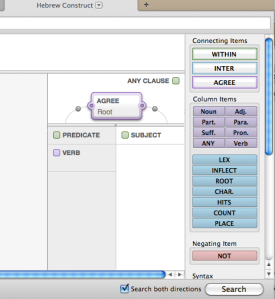

See the difference there? They put ‘still’ in the second slot so that it would be read unambiguously as an adjective. Why didn’t the KJV just copy this exactly? My best guess is it has to do with the word-for-word thing. The Hebrew is קוֹל דְּמָמָה דַקָּה with דְּמָמָה the word usually translated as ‘still’. Since the order of adjectives is ‘still’ then ‘small’ in the Hebrew source, the KJV translators opted for “still small” in the English despite the possible ambiguity.

_______________

* Unless I am sitting there, of course. Note also the legitimating function of referring to them as “the original languages”.

** Note that this Hebrew phrase is interesting in its own right, but that is a post for another day.

** Baker cites this translation later, but doesn’t seem to take it into account. I am also confused as to why he added the caveat “in the English translation” above. Is he suggesting that the translation somehow has its own meaning independently of the source text?